Poet or Prophet:

Percy Shelley as the First Agnostic

The structural pillars of modern society stand firmly on the shoulders of our past’s most forward thinkers.

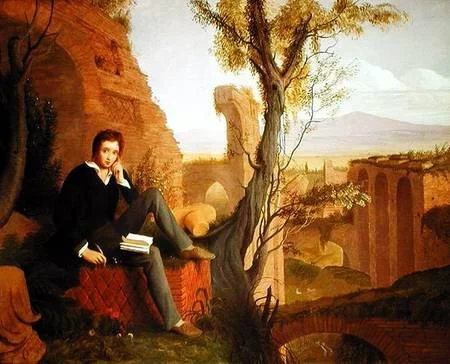

But in order to make the progress we now take for granted happen, a boldness and bravery of spirit were required; particularly in the realm of religious history, where doctrine and dogma were notoriously rigid. To question the church in the early 19th century was, for most, an unthinkable concept, but for English author and poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, to question was a necessity. Outspoken and inquisitive with a passion for truth, much of Shelley’s work revolved around his search for divine answers and his self-proclaimed Atheism. When studying his work in the current age, it is evident that Shelley’s religious perspective was ahead of its time, and that his reputation as an Atheist was merely a placeholder for his progressive ideas that had not yet been defined as Agnostic.

In order to analyze how Shelley’s works were pioneering in their religious ideals, we must first define and understand the difference between Atheism and Agnosticism. Atheism, a term first conceived in the 16th century, has had a plethora of sects, philosophies, and interpretations since its inception, but for our purposes here, can most simply be defined as a disbelief in God or Gods. What is necessary to note about this definition is the meaning of the word “disbelief” – this word denotes not an uncertainty in God’s existence or a questioning of doctrine, but a finite and absolute lack of faith; the antithesis of belief. Agnosticism, which did not see its inception until more than 30 years after Shelley’s death, provided a much more dynamic and provisional definition for those like Shelley, who fell somewhere between the rigid extremes of complete Atheism and the unwavering faith of Christians at the time. First introduced in 1869, English biologist T.H. Huxley coined the term Agnosticism in order to describe those who, like him, “Confess themselves to be hopelessly ignorant concerning a variety of matters, about which metaphysicians and theologians, both orthodox and heterodox, dogmatize with the utmost confidence” (qtd. in Draper, Zalta). The important difference here lies within the lack of certainty and assuredness that a God or Gods could exist or not; implying that because there is no way to empirically prove such a matter beyond any doubt, one could not ascribe themselves to a complete confirmation or denial of either perspective. It is here within this doubt that the forward-thinking nature of Shelley’s work is evident, and when analyzing his lifelong struggle with the question of God, one can see that his search for such answers categorizes him not as an Atheist as his reputation suggests (or even as he thought himself to be), but as one of the first-ever Agnostics of the era.

Rebellious and imaginative from childhood, Shelley’s curious nature and search for spiritual meaning were given room to blossom when he entered Oxford as a young adult. Indulging in his desire to answer life’s most complex questions, it was while studying at university that Shelley authored the essay, “The Necessity of Atheism” with fellow classmate Thomas Hogg; a controversial piece of prose that would eventually result in his expulsion from Oxford in 1811. However, despite its title, the contents of this piece are much more akin to what would later become Agnosticism, and contend not against the existence of God, but rather that the teachings which claim to prove God’s existence were unconvincing. Shelley builds upon the seeds of these thoughts in his later essays, such as his 1817 work, “Essay on Christianity,” in which he describes Jesus as having “The imagination of some sublimest and most holy poet;” whose writings are meant to be interpreted with figurative open-mindedness --as metaphorical expressions for goodness and virtue-- as opposed to rules to be followed literally as the Christian church imposed (qtd. in Hall 130). He goes on to suggest that even the word for God itself should be examined through a figurative lens, asserting that God is not some static entity casting judgements from above, but rather “A common term devised to express all of mystery or majesty or power which the invisible world contains” (qtd. in Hall 130); whose meaning is determined by the hearts and minds of its interpreter, not defined by scripture. Such reimagining of previously indoctrinated terms would continue to present themselves in Shelley’s works, and stand as testament to his pioneering impact on the evolution of Agnosticism, most notably in his renown poem, “Hymn to Intellectual Beauty.”

It is in this poem that Shelley’s beliefs are most clearly presented as a true antecedent to Agnosticism. Throughout the piece, Shelley describes his lifelong relationship with religion and spirituality, focusing on his search for validation of God and the fleeting nature of faith – describing it as only a visitor whose mysteries evolve and change as their perceiver does. Preoccupied with the inconsistencies of his emotions, Shelley describes how the mutability of life and the presence of doubt make him unable to devote himself to religion; instead, he dabbles in the mystical and the mythological, and creates his own solutions to the cosmic questions that go unanswered. This is best expressed in the poem’s third stanza, when in his frustration at the lack of clarity and fulfillment religion provides, he writes:

No voice from some sublimer world hath ever

To sage or poet these responses given-

Therefore the name of God and ghosts and Heaven,

Remain the records of their vain endeavor. (Shelley 25-28)

Here we can see Shelley’s dissatisfaction with religious doctrine’s claim to ubiquitous accuracy, because when put to question, these titles of God and Heaven are no less arbitrary than the interchangeable names given to countless spiritual entities and religious deities throughout history. In realizing that such titles and dogmas are transposable (and therefore, trivial), Shelley creates his own narrative for belief, and continues to express his ever-changing perspective and eternal doubt in religion throughout the rest of the poem. When analyzing the meaning within his work, author Judith Chernaik explains that in writing this piece, Shelley is attempting to “Create a personal and secular myth, to deny the authority of dogma or Scriptural revelation…while implicitly granting the validity of the irrational yet profound human needs that traditional religion claims to satisfy” (Chernaik 36). What Chernaik describes here truly encapsulates Shelley’s vision, he is enlightened enough to see the falsehood of the church’s absolutism, and uses his own literary and spiritual knowledge to rewrite the meaning of belief in his own terms.

Shelley would continue to discover new truths and redefine outdated doctrines throughout the rest of his life. And although Agnosticism would not arise until after his death, his courage and conviction in speaking out against the religious norms of the era would help to mold the minds of those like Huxley, who would eventually give Agnosticism its name and place in history. Shelley’s ability to speak honestly and vulnerably would lead his work to stand the test of literary time and continually impact writers, poets, and forward-thinkers to do the same; and although influential, the most integral aspect of Shelley’s life and work was not in his capacity to others, but in his unwavering devotion to asking life’s most profound questions, and being true to himself in the search for their answers, no matter what the cost.